How should we teach applied behavioural science?

- Elina Halonen

- Dec 10, 2022

- 4 min read

Updated: Dec 16, 2022

In the past couple of months I've been increasingly reflecting on the best way to train and upskill non-experts when it comes to behavioural science - for various reasons, it's a complex challenge and there's no one way to do it. In this process, I realised that designing effective learning experiences is similar to designing behavioural interventions: it's relatively easy to give people knowledge, but it doesn’t necessarily change their behaviour.

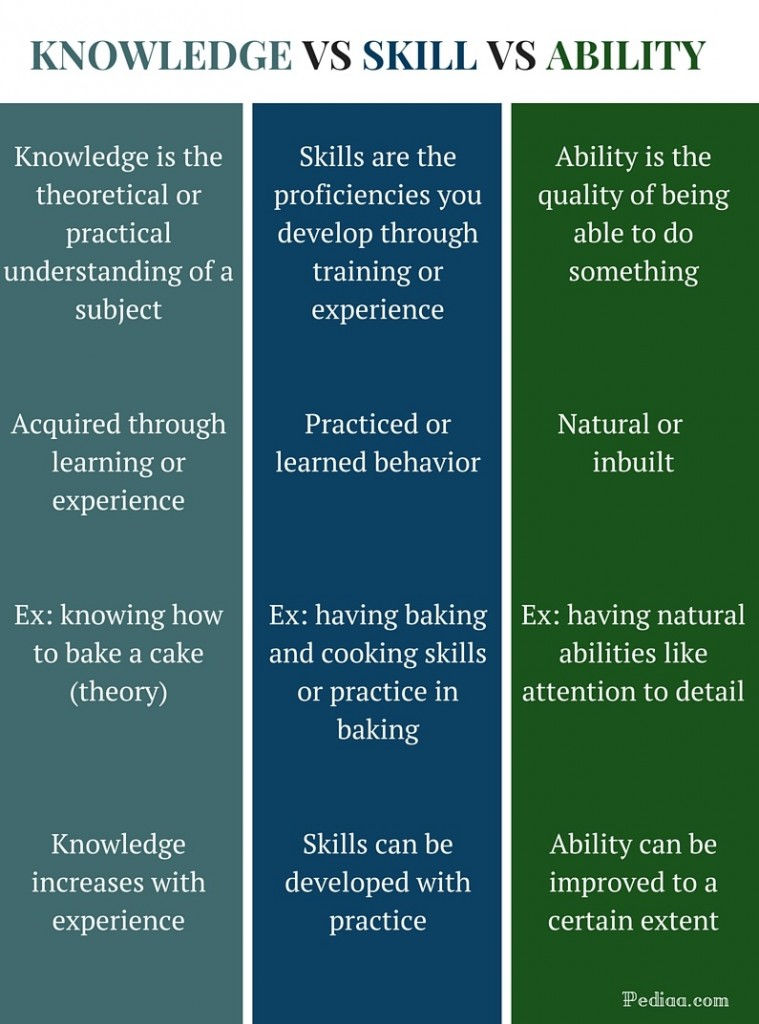

Teaching applied BeSci comes with some unique challenges: we are simultaneously trying to teach a new way of thinking (a skill) and help people digest a lot of new, complex ideas (knowledge) much faster than they would in a university course with months of weekly sessions.

Typically, those who are designing learning materials are experts, but what exactly does that mean and, more importantly, how do you help people develop it?

The challenges of developing expertise Expertise is best perceived as a continuum from novice to expert, with varying levels of fluency in the skill or knowledge about a specific field. One key characteristic of experts is that they have well-organized knowledge that is grounded in their field’s foundational concepts and oriented towards supporting understanding as well as recalling facts. The knowledge of experts is organized in conditional relationships and patterns that they can recognize, which makes it easier to recall relevant knowledge – and in fact, this ability is a core skill of an experienced practitioner of behavioural science. The biggest challenge here is that developing knowledge largely depends on what you already know and what you are learning – and because novices lack this fluency in recognizing patterns and problem-solving strategies, it's much harder to add new knowledge to what they already know. If we're aware of this challenge, we're in a better starting position for helping people develop their knowledge into expertise efficiently and effectively. Another common challenge for non-experts is retaining new information because you struggle to relate to your existing knowledge structures. For example, it is much easier to learn Spanish or Italian if you already speak French because you can relate new grammatical rules to ones you have already learned. It is especially hard to see patterns between fundamental principles in a field which often leads learners to develop an idiosyncratic combination of theories and concepts that might work in one context but does not transfer well to real life practice. However, it can be difficult to learn from experts because their fluency in the knowledge hides the same strategies that a novice needs to learn. To make things even more challenging, these strategies are often invisible even to the experts themselves because they have become so fluent they are second nature to them.

So, how do we solve this challenge?

There are several things we can do to help novices develop their BeSci expertise:

We make thinking more visible by designing learning activities in a way that allows people to make the processes of their thinking visible as well as the conclusions.

We model expert thinking by making their strategies and techniques more explicit by using techniques such as contrasting cases to illustrate specific points, and move from simpler to more complex examples as the learners’ understanding deepens.

We pay attention to the existing knowledge, skills and beliefs our learners bring to the learning environment and be clear about the learning goals to create strong foundational structures to build future learning on.

We can also use tools like Bloom’s Taxonomy (1956)* to understand the process of learning, and how we can design more effective learning applied BeSci experiences.

Most learning experiences only include the first two steps of Bloom's taxonomy: enabling learners to gain more facts and possibly explain ideas to others - however, learning to apply behavioural insights effectively requires raising the bar for the learning experience to applying, analyzing and evaluating. Ideally, when we are e.g. upskilling colleagues in an organisation, we need to help people learn how to use information in new situations, draw connections between ideas - without that, our impact in an organisation will be limited.

Broadly speaking, we need to shift from trying to cover more content to "uncovering" the big ideas within the content because by focusing on fewer, bigger ideas we can avoid superficial learning and allow people to engage in active meaning-making processes that are crucial for effective learning. Ultimately, this means orienting our learning goals towards a smaller number of conceptually larger ideas which aligns with how experts tend to organize their knowledge around core concepts. This allows the learners to understand the underlying general principles that can be applied to problems in different contexts and identify the core ideas that can serve as a conceptual lens for connecting discrete facts. In short, we should use big ideas to frame our teaching and include the details that support those big ideas. This also leads to a second shift from less telling and more meaning-making so that we move from being “sage on the stage to guide on the side”. What does this look like in practice? Well, it's a work in progress! I'm currently mapping out different potential lenses, and will share some tips in a future post but in the meantime I'm interested in hearing what approaches other people have taken - what works, what doesn't?

UPDATE:

A lively LinkedIn discussion highlighted some new ideas to explore and I wanted to note them here for future reference in case they help someone else, and I'm not sure when I might have time to write about them:

Backwards Design (Understanding by Design)

Knowles's Principles of Andragogy (Adult Learning)

Five-Stage Model of the Mental Activities Involved in Directed Skill Acquisition

* The revised version of Bloom's Taxonomy (2001, below) added action words that we can also use as guidelines when design learning experiences:

_edited.png)

Comentarios